GIVE ME THE SECRETS OF A MASTER MASON

by WM Rick Cave

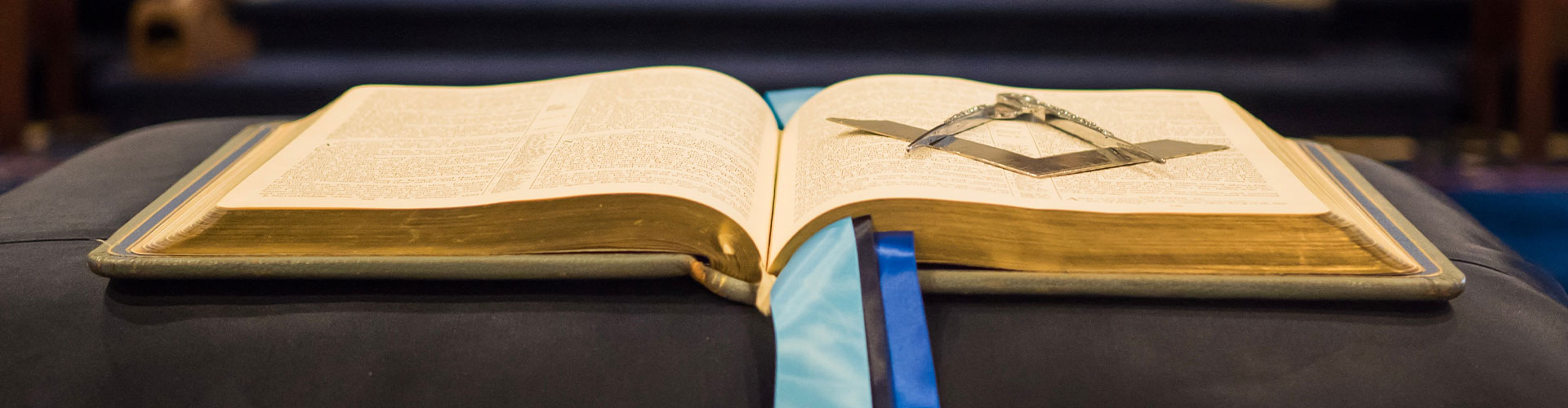

In the second half of the third degree, the candidate is confronted by the three ruffians. Each one demands of him the “secrets” of a master mason. The ruffians say they were promised the secrets of a Master Mason, when the Temple was complete, so that they might travel to foreign lands, work, and earn Master’s wages. The candidate is told later in the degree that the Master’s Word has been lost with the death of Hiram Abiff, but King Solomon substitutes a word to be used “for the regulation of all Master Masons lodges until future ages shall find out the right”. By the end of the third degree, the newly made Master Mason has a password and grip to enter a lodge of Master Masons; and he has learned the Grand Masonic Word, and how it is given between brothers. He also learns how to signal distress and enlist the aid of fellow brother Masons, should that be necessary. Are these words, grips, tokens, and signs the “secrets of a Master Mason”? My premise is that they are not the true secrets of a Master Mason, and that the secrets of a Master Mason are individual and must be learned by each brother by walking the path we call Freemasonry.

The Masonic ritual has been recorded in many different books that are available in public libraries and bookstores. One such book, Born in the Blood, the Lost Secrets of Freemasonry by John J. Robinson, 1, not only describes our degrees, but also gives the passwords, including the Grand Masonic word. The author discloses these “secrets” to show his theory of the origin of the craft and the words themselves. If our passwords, grips, and rituals are readily available in print to anyone desirous of learning them, are they truly our “secrets”?

Bro. C. Bruce Hunter, in his paper in the Transactions of the Quator Coronati Lodge No. 2076, Volume 117, states that when Freemasonry made itself public in the beginning of the 18th century, most members of the craft did not take the “secrets” seriously. “Any secrets that originated as early as the 11th or 12th centuries, be they architectural or military, were certainly obsolete when the Craft entered the modern era. This may explain the levity with which the rank and file were apparently treating their traditional secrets in the 1720’s.”2 It appears that when Masonry changed from being an operative craft to a speculative craft, the “secrets” of the craft also changed. The secrets of building stable, beautiful edifices were left, and other philosophical secrets were sought.

If our secrets are not words, grips, or signs, i.e., material; then they must be immaterial. A look at our ritual will be helpful. In the first degree the Senior Deacon asks the Stewards how the candidate expects to gain admission, and the answer is partially that he is well recommended. In the second and third degrees, the answer to the same question is, “By the benefit of the pass”. We later hear that the candidate does not have the pass, but in turn the Senior Steward and then Senior Deacon will give the pass for him. Entrance to the lodge to be initiated is dependent upon another brother or brothers, not the knowledge of the candidate himself. In the first degree, the newly made brother is asked to “deposit something of a metallic kind” to commemorate that he has been made a Mason. Being divested of all metals, he cannot. He is instructed that this request is to teach him to contribute to brothers who are in need so long as it does not cause inconvenience to himself. Again, we see the theme of one brother helping another. In the second degree, the brother learns about education, the various disciplines of learning, and how they relate to both operative and speculative masonry. The lecture by the master on the letter “G” relates the importance of geometry and willing subjugation to Deity. In this degree, the theme of learning to improve oneself, and following the will of Deity, not our own will is illustrated.

The lesson and drama of the third degree demonstrate to the candidate that since death is a part of life, there is even more reason to live with integrity. The explanation of the five points of fellowship, reinforce the idea of assisting each other through life, when needed, as brothers should. The instruction of the proper use of the trowel, teaches us to work in harmony together: an important ingredient in accomplishing any goal.

Ideas of how to live as a man are distilled into the three degrees of ancient craft masonry. Psychologists tell us that a person must hear something about fifteen times before it is understood. So, every time a man witnesses or takes part in one of the degrees, he may “see” something new or have a revelation about how he can be a better man, how he can change his life for the better, or how he may help a brother. And, improving himself translates into improving his family, and by extension, his community. So, we come to see that the true “secrets” cannot be given to any brother. They must be earned by walking the path of a Masonic life of trying to “imitate that celebrated artist” and incorporating the lessons of the degrees, as they apply to each individual brother’s life. Therefore, Hiram Abiff cannot give the secrets of a Master Mason to the Ruffians. Each man must find the secret of how he should best live, himself, while “laboring” on earth. Hiram’s admonition to the Ruffians that they should wait with patience until the proper time is described in a poem by Robert Frost entitled “Snow”. In closing, here are Frost’s lines that describe to me how we learn and grow from the rituals of Masonry:

“Things must expect to come in front of us

A many times-I don’t say how many-

That varies with the things- before we see them.

One of the lies would make it out that nothing

Ever presents itself before us twice.

Where would we be at last if that were so?

Our very life depends on everything’s

Recurring till we answer from within.”

References:

Hunter, C. B.