Major General Richard Montgomery

Namesake of Montgomery Lodge No. 13

“He was brave, he was able, he was humane, he was generous . . .” This characterization of Montgomery by Lord North after word of his death had been received in the British parliament basically says it all. He was variously described as tall, of fine military presence, of graceful address, with a bright, magnetic face, winning manners, and the bearing of a prince. Of the three Continental Army Brigadier Generals who had been officers in the British army, Montgomery, though perhaps inferior to Charles Lee in quickness of mind, was much superior to both him and Horatio Gates in all the great qualities which adorn the soldier. He was a young man of superior talents and high spirits, a martyr to his love for liberty, who fought bravely and boldly in defense of his adopted country.

Richard Montgomery, whose lineage can be traced back to Scotland, was, by most accounts, born on December 2nd, 1738 (although a few sources list his birth year as 1736). All agree he was born in Swords (near Feltrim), County Dublin, Ireland. The Scottish Lady Montgomery had established linen and woolen producing mills in Ireland at the end of the 16th century to produce tartans. These mills were almost exclusively managed and staffed by members of the Montgomery clan who settled and remained in the areas near Dublin. Richard’s father was a member of British parliament and apparently a man of some means. Accordingly, Richard was educated, first at St. Andrews and later, at Trinity College in Dublin.

At the age of 18, he enlisted in the 17th infantry of the British Royal Army as an ensign. During the French and Indian War, he served at the siege of Louisbourg and at Lake Champlain. After the fall of Montreal, he was transferred to the Caribbean, where he oversaw the capture of Martinique and Havana. He was promoted to Captain at the age of 24 and returned to England at the age of 26. During the period which followed, he became increasingly sympathetic to the American colonists’ plight and their struggle for liberty. He also became known for his opposition to tyranny and the Stamp Act.

Frustrated with lack of advancement (probably due to politics at the time, as he had become friendly with many of the liberal members of parliament),he sold his commission at age 34 and moved to New York, purchasing a farm 13 miles North of New York City. Shortly after his arrival in his adopted country, he married Janet Livingston, the daughter of a wealthy Judge, Robert R. Livingston, with whom he had become acquainted several years earlier. Incidentally her brothers and father were members of the Craft. More than a decade after Montgomery’s death, his father-in-law, Robert R. Livingston would, while serving as Grand Master of Masons of New York, administer the Oath of Office to President George Washington at his inauguration on February 4th, 1789. Montgomery purchased a “handsome” estate on the banks of the Hudson near Kingston, which he named Montgomery Place. Although he set about making plans for the construction of a mansion there, he spent the few years of his married life in his wife’s residence of Grassmere near Rhinebeck, New York.

Married life apparently agreed with him and he was reluctant to leave his wife’s company, but nevertheless, his reputation and high standing resulted in his being elected as a delegate to the 1st Provincial Congress in New York City in May 1775 at the age of 36. Within a few weeks, in June 1775, he was named one of eight Brigadier Generals of the newly formed Continental Army – and the only one not a New Englander. Reluctant to leave his wife and farm, but spurred on by his sense of patriotism to the American cause, he wrote “the will of an oppressed people . . . must be respected.”

Among his many attributes, he apparently was a capable leader as he took the troops which he described as “the sweepings of society and officers who he characterized as ‘vulgar’ and shaped them into an effective army as they advanced down Lake Champlain. The hardships he faced in this endeavor led one historian to assert that “Nothing but devotion to his country could have made him continue in the irksome command. Hitherto his career had been successful, and he was ambitious of closing the campaign by some brilliant achievement which might at once elevate the spirits of the Americans and humble the pride of the British ministry.”

He was assigned to serve as second in command to General Philip Schuyler, who became ill almost immediately, resulting in Montgomery assuming entire command. He overcame the mutinous conduct of his soldiers, lack of proper munitions, and incidental suffering to prevail in a brilliant campaign that resulted in the capture of the fortresses of St. John’s and Chamblee on 19 October and the capture of Montreal on 11 November 1775. At St. John’s, the colors of the 7th fusiliers were captured – the first taken in the war. These victories notwithstanding, he astutely realized that unless the city of Quebec was overcome, Canada would not truly be won and advised General Washington of the same. Accordingly, with what troops he could muster, he pressed on to join up with General Benedict Arnold, with the hope of defeating the British in Quebec.

On December 2nd, his 37th birthday, he rendezvoused with Arnold near Quebec. On December 9th, Montgomery was promoted to Major General, a fact of which he would never learn. The expiration of enlistments of many of the troops, weariness, illness, and a lack of munitions and supplies were all responsible for greatly diminishing the number of effective fighting men under both his and Arnold’s commands. He knew that he, now with 300 men and Arnold, whose forces were reduced to 600, were racing against time: The term of enlistment of most of his men was to expire on the first of January 1776, smallpox was prevalent in the camp and winter was upon them, precluding a prolonged siege of the city. During December, heavy snow fell in Quebec and bone chilling cold set in. Accordingly, Montgomery called a Council of war, where it was agreed to carry an assault against Quebec to commence on December 31st 1775. In the assault, he had many things in his favor including a full moon, a drunken British army & the snow. Unfortunately, there was one thing against him – an American deserter had tipped off the British as to the planned attack.

At about 0400 hours, the attack began. Montgomery led from the front yelling to his men “Push on brave boys, Quebec is ours!” After breaching the first barricade, he continued to lead exclaiming “Men of New York, you will not fear to follow where your General leads.” A few moments later, while he, his aide-de-camp and a battalion commander were investigating a rough barricade that had been thrown up by the British, the three of them were felled with the first and only load of grape shot fired from a British cannon. Thus he became the first Major General to die on the field of battle in the Revolutionary War. The men under his command fell back in disarray and scattered uselessly. A short time later, Benedict Arnold, while leading a second attack, was wounded by a musket ball which tore into his leg but he survived. He was carried from the field to safety at some point distant. Captain Daniel Morgan assumed field command of Arnold’s troops but was persuaded to wait for reinforcements that would never arrive. By the time Morgan ordered his men to advance, the advantage had swung to the British and most of the force was either captured or surrendered.

Montgomery’s body was found by the British and the commanding British officer, General Guy Carleton, himself a Mason, conducted a burial in Quebec with full military honors. Montgomery’s remains would be interred there for 43 years until 1818 when, by “An act of honor” passed by the NY legislature, Sir John Sherbrooke, governor general of Canada was requested, and agreed to allow Montgomery’s remains to be disinterred and conveyed to NYC where they were re-interred on July 8, 1818 in St. Paul’s chapel near a marble monument that had been commissioned by the Continental Congress to honor his memory. The monument, ordered in France by Ben Franklin was inscribed thusly: “This monument is erected by order of congress, 25th January, 1776, to transmit to posterity a grateful remembrance of the patriotism, conduct, enterprise, and perseverance of Major-General Richard Montgomery, who, after a series of successes, amid the most discouraging difficulties, fell in the attack on Quebec, 31st December, 1775, aged 37 years.”

Upon news of his death, enemies and friends alike paid tribute to his valor. In the British parliament, his friends remembered and supported him. Even a detractor, Lord North, acknowledged his virtues and paid tribute to him with the statement: “He was brave, he was able, he was humane, he was generous, but still, he was only a brave, able, humane, and generous rebel.” In response, his friend Charles James Fox retorted “The term of rebel is no certain mark of disgrace. The great asserters of liberty, the saviors of their country, the benefactors of mankind in all ages, have been called rebels.” In the Colonies, the city of Philadelphia was said to have been in tears –“every person seemed to have lost his nearest friend.” Congress proclaimed their grateful remembrance, respect and high veneration and desiring to transmit to future ages a truly worthy example of patriotism, conduct, boldness of enterprise, insuperable perseverance, and contempt of danger and death had ordered the erection of the monument to his memory as noted above.

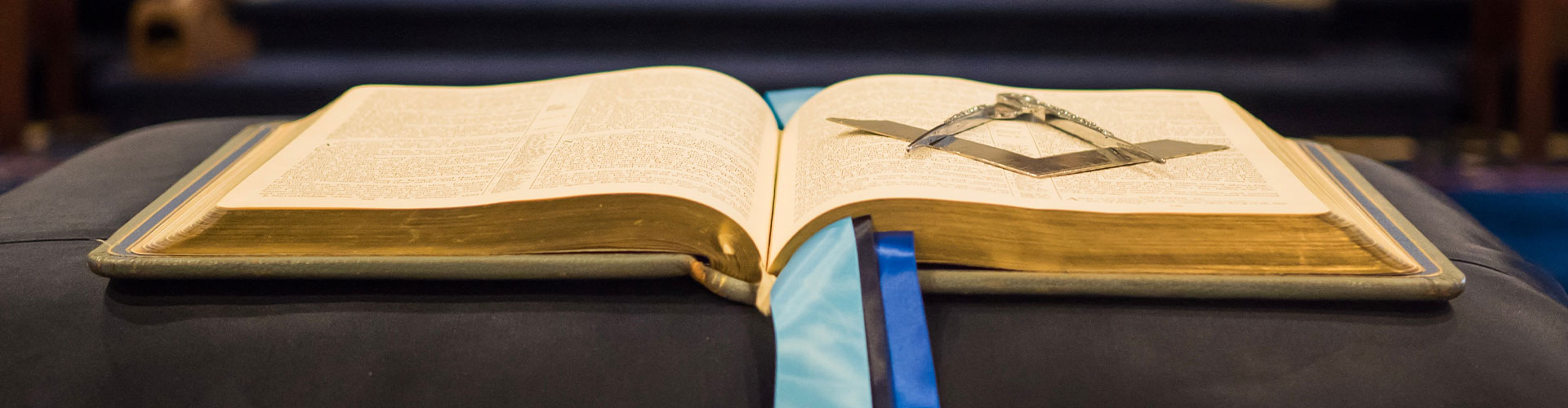

Brother and General Richard Montgomery is listed as a member of Mount Vernon Lodge No. 3 in Albany, New York. The Connecticut historian, James Royal Case, in his book Fifty Early American Military Freemasons, states his belief that he was initiated in the traveling Lodge of Unity No. 18 under Irish registry. As this military Lodge was attached to his 17th Regiment of Foot where he began his military career, this seems to be a logical conclusion.

As an early American martyr, he was toasted at Masonic meetings as “One of the three eminent Masons who fell in liberty’s cause – Montgomery, Warren and Wooster.” According to Lodge records, this toast was given in American Union Lodge, a Connecticut military Lodge, on the 25th of March 1779 and again on June 24th 1779 during St. John’s ceremonies which were attended by Brother and General George Washington. Lodges in Massachusetts, New York and Connecticut are named in his honor. In the drama of the Scottish Rite 20th degree, Montgomery is mentioned as a Brother Mason who died in the attack on Quebec. Numerous counties, cities and towns throughout the United States are named in his memory and honor – a gallant Irishman, a martyr to his love for liberty and who fought bravely in defense of his adopted country. Modern Masons could do worse than to follow the example set by this distinguished Brother.

Presented to the members of Montgomery Lodge No. 13 on January 15th, 6003 by Brother Charles W. Yohe, Most Worshipful Grand Master 5996.